UWinnipeg Urban and Inner-City Studies Associate Professor Julie Chamberlain is wrapping up two multi-year research projects – one working to make city and provincial spaces more inclusive, and one that helps neighbourhoods access safety resources.

Supporting community

Both are community-based research projects – meaning the research questions didn’t emerge from academia, but came directly from community organizations expressing a need.

“It’s very rewarding to do community-based research,” Dr. Chamberlain said. “The opportunity to use my skills, my experience, and my knowledge to serve my community is deeply, deeply meaningful.”

Dr. Chamberlain co-leads the Community-Based Research Training Centre, which is a joint project of Manitoba Research Alliance and the University of Winnipeg Research Office. The Centre provides researchers with the skills to tackle research projects in the community.

“This approach to research really brings the University to street level,” Dr. Chamberlain said. “My work, and the work of my students, is being influenced by practical, concrete questions that are happening in public spaces. And, on the other hand, some of the resources and the insights of scholarly work are more accessible to the neighborhood.”

Community safety toolbox

Since 2022, Dr. Chamberlain has been working with the South Valour Residents Association to help them better understand how to take action on community safety in their area.

After publishing a report in 2023 of possible strategies that can be implemented in communities, the focus of the project shifted to looking at how we talk about safety and exploring how to put anti-oppressive principles into action at the neighbourhood level.

I think some of these resources will be invaluable, especially for community groups that are kind of running on a shoestring.

Dr. Julie Chamberlain

“There’s an opportunity to think critically about what makes us uncomfortable and why it makes us uncomfortable,” Dr. Chamberlain said. “If we just sort of fall back on our kneejerk fears and kneejerk reactions, then sometimes we can make pretty bad and very exclusive decisions as neighbors and as neighbourhood associations.”

For the past two years, Dr. Chamberlain and her team have been engaged in a participatory-action research project – taking action on the issue of safety in the neighbourhood, reflecting, and documenting their process and progress.

“It ended up that the focus was very strongly on the idea of building social capital and building relationships in the neighbourhood,” she said. “Now, we’re starting to share some of the things that we’ve created.”

Dr. Chamberlain’s team recently launched a Community Safety Toolbox, which is available on the University of Winnipeg website. It’s a resource that offers guides, templates, examples, and plans, mainly to support community development in Winnipeg neighbourhoods.

“I think some of these resources will be invaluable,” Dr. Chamberlain said, “especially for community groups that are kind of running on a shoestring and will benefit from some of the groundwork already being done.”

The toolbox provides advice on how to hold a conversation about safety in your neighborhood in an inclusive way, asset mapping, volunteer engagement, and more.

“We’re also doing some policy-oriented writing about the insights from the project about what the city could be doing, what the province could be doing, to support this kind of work and to support a greater sense of safety, particularly in West End Winnipeg,” Dr. Chamberlain added.

wâhkôhtowin

Dr. Chamberlain is also co-investigator (along with Christine Mayor from the University of Manitoba) for a community-based research project that addresses safety and inclusion through shifting our perspectives about security.

This research looks at data collected from Community Safety Hosts who, in addition to being trained as security guards, have taken hundreds of hours of training in nonviolent crisis intervention, harm reduction, and in understanding resources that are available through Winnipeg community organizations.

“So, rather than focusing on just securing space,” Dr. Chamberlain said, “they were trained to pay attention to relationships, to pay attention to the people who are in the space, and to prioritize the well-being of people, specifically in spaces of access.”

Community Safety Hosts have been working since 2021 in city and provincially-run spaces where community members might need access to services, for example libraries, unemployment offices, and social services buildings.

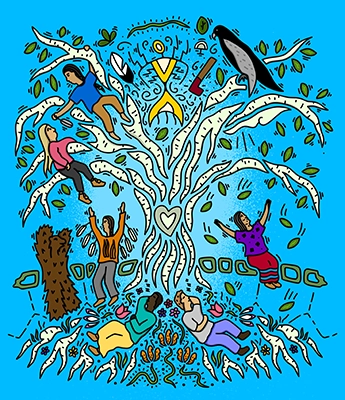

“It’s very much an Indigenous-led program, an Indigenous-initiated model,” said Dr. Chamberlain. “And, at the heart of the training of the Community Safety Hosts is this concept of wâhkôhtowin, which is a Cree philosophy and a worldview that says that we are all interconnected, that everything in the universe is interconnected.”

“We all live and work in this interconnected web of relationships, and that requires certain things of us. If we’re interconnected with everybody and everything, we have responsibilities to everybody and everything. And that then, should define how we treat other people and how we act in the world.”

Working closely with community members, the research project looked for the ways that wâhkôhtowin might appear in practice, and identified that Community Safety Hosts practice wâhkôhtowin in seven major ways.

Examples of the ways wâhkôhtowin was practiced include sharing with others to show kindness and concern, taking care of those who need protection and guidance, and giving people loving support without judgment or condemnation.

“What we could see is that when Community Safety Hosts are engaging, they’re problem solving for people or they are de-escalating situations before they get to the point where a security guard might be asking somebody to leave,” Dr. Chamberlain said. “And, often it does lead to people either being able to access what they came for or being able to stay in the space when they otherwise wouldn’t have.”

Dr. Chamberlain said Community Safety Hosts play a role that other staff are often not trained to do or don’t have the time to do. Since Community Safety Hosts are typically youth who have aged out of CFS care or have struggled with some of the things that they encounter in their daily work, they also bring valuable lived experience to the role.

“It’s a very rich picture of how they practice wâhkôhtowin,” Dr. Chamberlain said. “There are these seven overarching ways, and within that all of these very detailed, often quite beautiful, quite moving, sometimes very difficult stories about what that looks like.”

The full report from the research is available online. Dr. Chamberlain and her team also plan to create some policy pieces to accompany the report, with the hope that we will see more Community Safety Hosts working in more spaces in Winnipeg.

“People are people are struggling with poverty,” she said. “They’re struggling with mental health issues. They’re struggling, often, with substance use. And, we need models that instruct us about how to deal with these issues in caring and ethical ways.”