There’s a turntable in the University of Winnipeg’s TerraByte lab, but it’s for scanning plants, not spinning records.

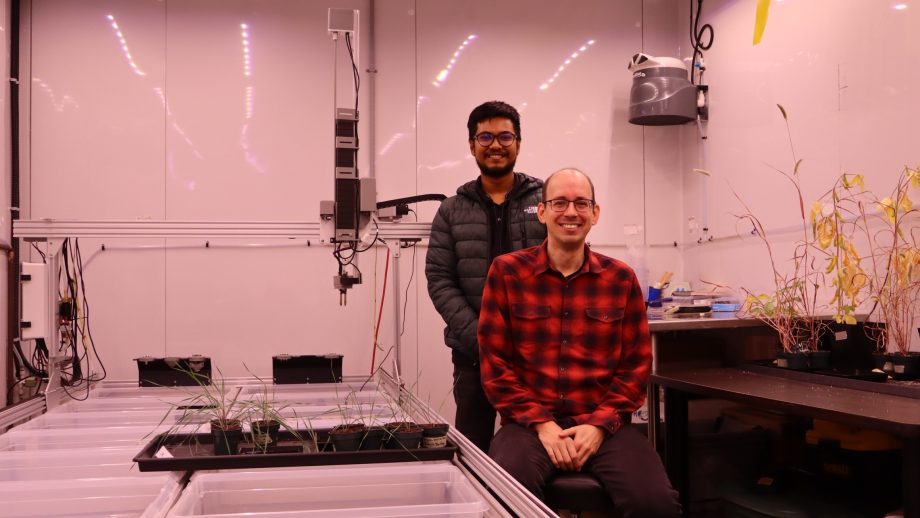

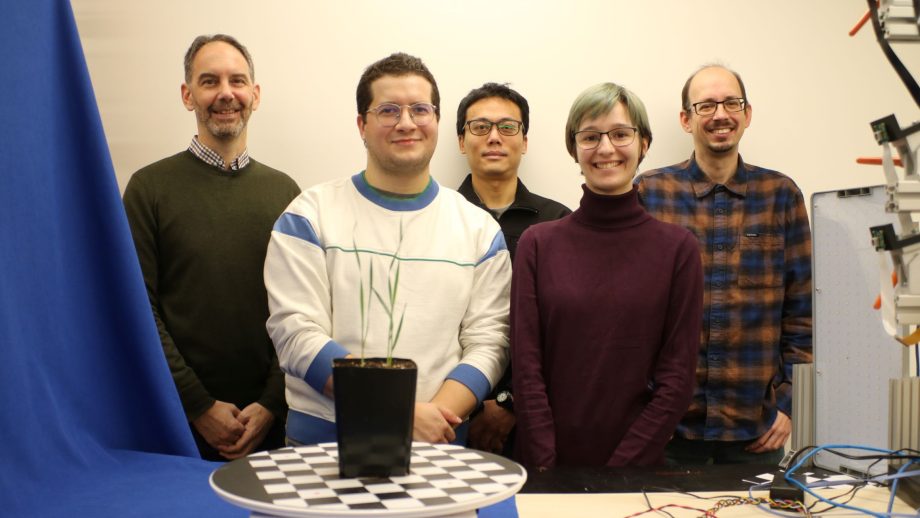

“You put the plant on the turntable and the plant rotates and you take pictures from four different camera angles and then you can build up 3D models,” explained Dr. Chris Bidnosti, Professor in the Department of Physics and co-founder of the TerraByte lab, an interdisciplinary hub for research exploring machine learning applications in agriculture.

Located at the intersection of physics, computer science, biology, and engineering, TerraByte is opening up new career possibilities for students and is also one of UWinnipeg’s most successful research programs to date, attracting nearly $5 million in external funding since 2018.

Plant scientists really love this thing.

Dr. Chris Bidnosti

In November, Dr. Bidnosti and colleague Dr. Michael Beck, Assistant Professor in the Department of Applied Computer Science, landed a two-year, $100,000 Innovation Proof-of-Concept (IPoC) Grant from Research Manitoba to scale up their research project, entitled “Low-cost photogrammetry to accelerate plant science and breeding.”

Photogrammetry is use of photography to develop 2D or 3D visual models of objects. It’s commonly associated with buildings, bridges, and other infrastructure. Dr. Bidnosti and Dr. Beck are exploring its applications in agriculture. They were inspired by museums that use photogrammetry to scan artifacts.

A 3D plant image is useful for researching everything from phenotypic traits and crop yields to a plant’s resistance to disease, pests, and drought. Much of today’s research in digital agriculture is taken up with concerns of global food security: population increases, climate change, and the emergence of herbicide-resistant weeds.

By bringing down the cost of a photogrammetry setup, the project has the potential to revolutionize the pace and accuracy of plant science, which still involves a lot of manual counting and measuring.

“So much plant science is still being done by hand and by visual assessment,” Dr. Bidnosti said. “It’s still about sending out a fleet of grad students with clipboards to eyeball.”

He and Dr. Beck want to produce affordable replicas of the photogrammetry prototype in the TerraByte lab, which was assembled for a master’s research project at a cost of about $2,000.

Their plan is to bring down the price point to around $1,000 and develop more user-friendly software to make the turntable easier to use. The low cost is achieved by using a line of camera modules called Raspberry Pi which were originally developed with educators and hobbyists in mind.

“There’s this technology gap for plant scientists,” Dr. Beck explained. “They might not even know that these technologies are out there, but they don’t have the bandwidth or capacity to really dig in to this.”

The setup costs far less than commercial 3D scanners, which sell for $70,000 or more, putting them out of reach for most plant scientists and breeders. The hope is that lowering the price point will make it easier for the technology to be adopted by research teams in Manitoba and across Canada.

“Plant scientists really love this thing,” Dr. Bidnosti said. “Your throughput increases by a massive amount and the quality of the data increases.”

Agriculture departments at the University of Manitoba and the University of Saskatchewan have already taken notice. It has also caught the eye of researchers of the federal government’s Morden Research and Development Centre in southern Manitoba, which researches cereal, pulse, and oilseed crops.

Affordable—and, one day, portable—photogrammetry could prove to be a foundational advancement that relieves a bottleneck that has long plagued plant science: the need for manual counts during time-sensitive stages of a plant’s growth.

“This is where people from computer science or physics can help close that gap,” Dr. Beck said, “so that plant scientists can be more productive and have their students do things that are more relevant to their research than spending two weeks walking through a field with a clipboard in hand.”

Replacing manual guesswork with readings that are rapid, accurate, and automated could help speed up the development of new plant varieties that are better suited to warmer environments and more resistant to diseases and pests.

Dr. Bidnosti called it a great example of “research to enable research”—developing solutions to first-order problems that, once addressed, open the floodgates for more research. While TerraByte doesn’t work directly with farmers, its advances may one day trickle into the agricultural sector’s marketplace.

“We don’t really promise stuff at the farm gate because we don’t do tractors or things on that scale,” Dr. Bidnosti said. “It’s outside our scope. But what we can do is work with agronomists and plant scientists. So, it’s a longer path to the farm, but it all leads to better plants.”

Dr. Bidnosti and Dr. Beck believe there are more bottlenecks in plant science that TerraByte may be able to address.

“Whenever we talk to a new person, they paint us a picture of a new problem we haven’t heard about before,” Dr. Beck said. “And we think, ‘Oh yeah, we can probably do something here about that.’”

He finds the collaborative, solutions-oriented work gratifying.

“This is the real fun of it where you have this interdisciplinary work where we meet all these people who are doing interesting things and we are able to help them out.”