Originally published in the Fall 2016 UWinnipeg Magazine.

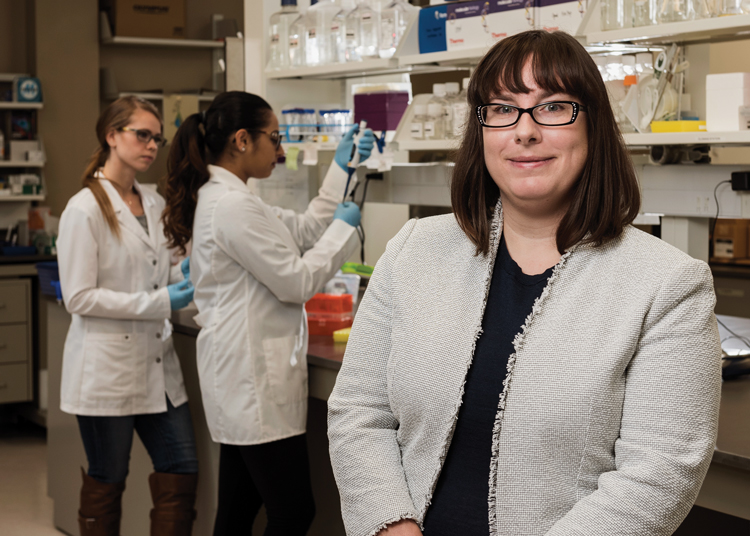

In Dr. Renée Douville’s office, four letters sit on a windowsill overlooking the atrium in the Richardson College for the Environment and Science Complex: N.E.R.D.

As a lover of Lego sets and The Big Bang Theory, Douville, an associate professor in biology, certainly has the credentials to back up the claim. But like most things in her life, she prefers to describe her identity in a scientific context.

“Being a nerd is about embracing the fact that you might be neurologically atypical, and you might not be like other people, and that’s okay,” says Douville, who was recently named UWinnipeg’s sixth Chancellor’s Research Chair.

Atypical biology also happens to be the focus of Douville’s research. Specifically, she is studying the relationship between our brains and human endogenous retroviruses (ERVs), a typically dormant group of viruses located in the human genome.

“Eight per cent of your DNA is made up of ERVs. That means viruses actually integrated their viral genome into your DNA a long time ago in your ancestors,” she states. “The question is: do they do anything? I think they do.”

What they do could have a significant impact on the way we treat neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric diseases like amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and schizophrenia, which have both been linked with an increased presence of ERVs. Douville’s laboratory has already succeeded in discovering a novel ERV protein with the potential to cause neuronal damage and inflammation in the brain. The challenge she now faces is convincing her peers these findings are more than a coincidence.

“For a long time people used to call this ‘junk DNA’, so they thought it did nothing; it was just there,” explains Douville. “It wasn’t a human gene, so it couldn’t be important. But actually human genes only account for 1.5 per cent of our DNA.”

While it can seem like an uphill battle, it’s not one that Douville is facing alone. She credits the success of her laboratory to the involvement of her student researchers.

“The students are the research; I would have nothing here if it wasn’t for the students. They’re the ones that are in there pipetting, doing the work, coming in on weekends, and making sure their cells are happy and healthy.”

Adam Campbell