Is it possible to reduce the amount of phosphorus being released from agricultural land and into waterways, such as Lake Winnipeg, during the spring melt?

Our goal is to keep phosphorus on the land and reduce losses from agricultural fields in the Lake Winnipeg watershed, which will help combat harmful algal blooms of the lake and mitigate negative effect on fisheries, wildlife, and tourism.

Dr. Darshani Kumaragamage

It’s a question UWinnipeg Professor Dr. Darshani Kumaragamage, Department of Environmental Studies and Sciences, and her research team are trying to answer.

In most parts of the world, erosion, and rain-driven runoff are the major pathways by which phosphorus from agricultural fields enter waterbodies. However, in cold climates like the Canadian prairies, flooding-induced phosphorus loss during the snowmelt period is the dominant transport mechanism of phosphorus from agricultural lands to water bodies.

“We’ve realized most of the management practices that are adapted elsewhere in the world are not effective in our situation,” Kumaragamage explained.

Over the last four years, the research team has looked at how soil amendments, such as alum, gypsum, and Epsom salt, would reduce phosphorus loss during spring snowmelt if applied in the fall.

Moving from the lab to the field

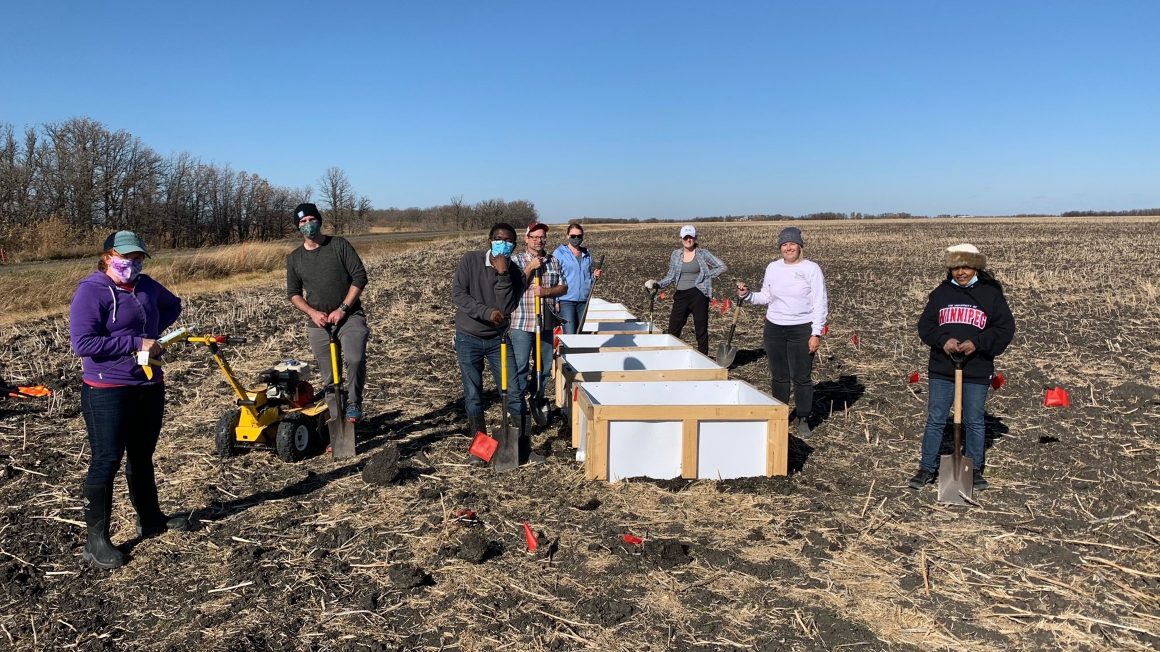

After receiving funding from Environment and Climate Change Canada through the Lake Winnipeg Basin Program, Kumaragamage and her team left the lab and took their research into the field.

The two agricultural fields selected for the study, which are both susceptible to flooding during spring snowmelt, are located in Morris and Randolph. Each site is seeded annually and was chosen from phosphorus hotspots based on Lake Winnipeg Basin Community-Based Monitoring Network data.

In the fall of 2020, Kumaragamage applied the amendments to the fields and installed runoff boxes to catch snowmelt in the spring. With further funding received from Manitoba Agriculture through the Canadian Agricultural Partnership Ag Action Program and Lake Winnipeg Foundation, the field study was continued for a second year. Runoff boxes were installed again in the fall of 2021, but without adding any further amendments.

“During the springtime, we went back to the fields, pumped out all of the snowmelt from each box every day, and then took a sample back to the lab to be analyzed,” she said.

Collaborators on this research included UWinnipeg’s Dr. Doug Goltz, Dean of Science; Dr. Nora Casson, Canada Research Chair in Environmental Influences on Water Quality; Dr. Srimathie Indraratne, Department of Environmental Studies and Sciences; and Master of Science student Madelynn Perry. External partners include Dr. Inoka Amarakoon, University of Manitoba; Dr. Henry Wilson and Dr. Ahmed Lasisi, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada; Chelsea Lobson, Lake Winnipeg Foundation; and Chris Randall, Seine Rat Roseau Watershed District.

The results

Despite little snow the first year of testing and too much snow the second year of testing, Kumaragamage says they were able to gather useable results.

According to their study, the tested soil amendments could potentially reduce phosphorus released to snowmelt runoff.

“Cumulative snowmelt in dissolved reactive phosphorus loads was significantly and positively correlated to cumulative snowmelt volume,” said Kumaragamage. “This study shows the potential of fall application of soil amendments, particularly Epsom salt, to reduce phosphorus loss to snowmelt from soils with high soil test phosphorus concentrations.”

These amendments would have to be applied every fall by farmers to their fields, Kumaragamage explained, noting it’s not required for the entire field, but rather low-lying areas where snow accumulates for a long period of time or the edges of fields where meltwater moves to a ditch.

Minimizing phosphorus losses with spring snowmelt from agricultural lands in the Canadian prairies will help protect water resources, such as Lake Winnipeg, without compromising food security.

“Our previous findings from laboratory and field studies point to the fact that some soil amendments are effective in reducing phosphorus loss,” said Kumaragamage. “However, the effectiveness depends on the soil type, land management history, and other environmental factors.”

Moving forward, the team aims to investigate whether applications of co-blended amendments would have a more consistent and greater effectiveness across different field sites in reducing phosphorus loss with snowmelt.

“Our goal is to keep phosphorus on the land and reduce losses from agricultural fields in the Lake Winnipeg watershed, which will help combat harmful algal blooms of the lake and mitigate negative effect on fisheries, wildlife, and tourism,” Kumaragamage said.