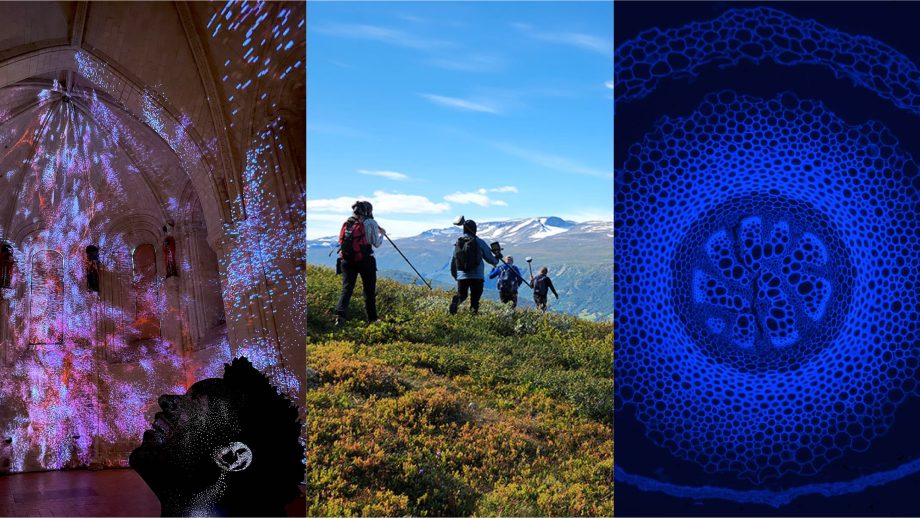

A dedicated award for students undertaking research in hard-to-access places is fueling efforts to protect lakes and watersheds around Flin Flon.

Dylan McKenzie is the 2023 recipient of The University of Winnipeg’s Remote Research Student Fund (RRSF), one of many student research grants available to UWinnipeg students.

Graduate and undergraduate students can apply for the $4,000 RRSF, which supports students undertaking research in remote locations where limited infrastructure, high costs, and isolation present barriers to conducting research.

McKenzie, who is in his second year of study in UWinnipeg’s Master’s in Environmental and Social Change (MESC) program, used the RRSF to gather water and soil samples in and around Flin Flon. The community of about 5,000 people is located on the Manitoba-Saskatchewan border.

“Doing northern research is tough,” McKenzie said. “You have to get a vehicle, gas, meals, and stay up there for a couple days to get your samples.”

McKenzie grew up in Winnipeg and completed a bachelor’s degree in Environmental Science in 2020. He now works as an aquatic biologist for an environmental consulting company, balancing part-time study with full-time employment. The job introduced him to remediation work on contaminated sites.

McKenzie’s advisors, Drs. Nora Casson and Srimathie Indraratne, helped McKenzie find an aquatic remediation project in Manitoba to study. The research will form the basis of his master’s thesis.

McKenzie travelled up to Flin Flon in late October. The community is home to a decommissioned metal smelter that was a source of atmospheric contamination for decades.

“There’s roughly 80 kilometres around the town that has levels of contamination ranging from very contaminated to less so,” McKenzie said.

Remediation work is needed to reduce levels of arsenic, cadmium, lead, copper, and zinc.

“All of those have a variety of health impacts, whether it be human carcinogens or detrimental impacts on the aquatic ecosystems in the area,” McKenzie said.

Traditional remediation methods involve dredging.

“That’s very expensive and often very destructive,” McKenzie explained. “In Canada, there’s very little research on natural remedies for remediation.”

McKenzie is studying the remedial uses of carbon-based materials like biochar, a lightweight black residue made from tree ash that acts as a metal-binding agent. Most existing research into the environmental applications of these organic materials has focused on their performance at room temperature. McKenzie wants to find out how well these organic agents perform in an aquatic ecosystem that sees 20-degree temperature swings over the course of a year.

He is especially interested in a natural remediation method called thin-layer active capping, which uses minerals and natural products to absorb metal contaminants.

“Dylan’s research is pioneering the remediation of heavy-metal-contaminated lake sediments in northern Manitoba, using eco-friendly solutions,” Dr. Indraratne said. “Legacy mining and ore smelting have left a detrimental mark on aquatic life due to the release of toxic elements. Dylan’s study is dedicated to exploring the efficacy of biochar in cleaning up contaminated lake sediments. His on-the-ground expertise in dealing with polluted environments has proven invaluable for this project.”

McKenzie said his research project wouldn’t have been possible without the RRSF.

“It’s not cheap to go up there and do that sort of research,” he said. “The only way it happens is with support. It’s not easy work, so not having to worry about the financial aspects of the research is a huge relief, especially when you’re trying to complete a master’s thesis.”

McKenzie hopes his research benefits Flin Flon community members, possibly by informing a long-term remediation plan.

“Binding these contaminants in the sediment, and then allowing natural processes to eventually cover them up, is helpful to people in the area,” he said. “They can maybe feel a bit better about fishing and swimming and using the vast number of lakes in that area.”